The houses featured leaded glass, fancy brickwork and five different facades in a mixture of brick and stone. The developers saved all the surviving trim, doors, mantels, floors, and sashes. New millwork was ordered to match missing pieces.

Windows over fireplaces had been bricked over. In the renovation, one original window was found and taken to a stained-glass maker, Wanda Greenwood [Hollberg]. It was repaired and copied in 19th-century glass for use in the other four buildings.

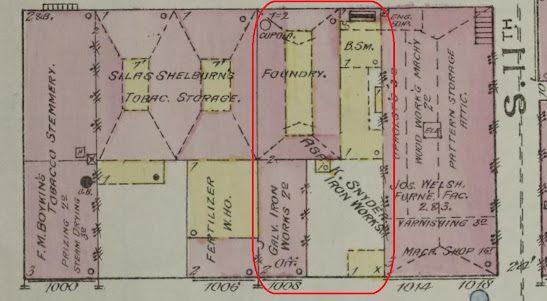

The north side of the 200 block of W. Main Street, Sanborn map, 1895, Library of Congress. Queen Anne Row is the five houses on the left side of the image, numbers 212 to 220. The other houses and the ones on the 300 block have all been demolished. We are lucky Queen Anne Row survived.

Handsome Improvements on West Main Street.

The large lot at the northeast corner of Main and Madison streets has been purchased by Mr. J. Cabell Brockenbrough, through J. B. Elam, agent of the estate of the late James M. Estes, deceased, for $9,500 and Mr. Brockenbrough has let the contract for the erection at once of five handsome stone and brick dwellings thereon. The plans, drawn by Major Black, and which have been adopted, show each house of different kind of stone up to the second story and the best oil pressed brick above, three of them having handsome towers, each having nine rooms and all modern conveniences. The contract provides for completion by the 1st of October. Mr. John Amrhein, general contractor; A. J. Brown, stone-work; J. T. Maynard & Son, brick-work; Asa Snyder, galvanized iron-work, and T. M. Laundors, plumbing and gas-fitting.

Mr. J. B. Elam is the agent for the rental of these houses.

The Architect.

The Lichtenstein Building, 29 N. 17th Street, corner of 17th and E. Franklin St. The image on the left shows the facade on 17th Street, and the right is the side facing E. Franklin St. Built 1878, designed by Bernard J. Black. It sits opposite of the 17th Street Farmer's Market.

"furnished with hot and cold water, gas, bathrooms, an elevator, and all other modern improvements, comforts, and conveniences. The parlor and other mantels, fireplaces, &c., will be of the most elegant description. The front will be of the best stock-brick, and the windows of French-plate glass. The windows will be fitted up with granite arches and sills."

Rare real-photo postcard view of the "D & E Mittledorfer" dry goods store, 217 E. Broad St., early 1920s. It was designed by Bernard J. Black. The new building replaced a brick structure. Black described the building in an article in the Richmond Dispatch, published April 4, 1890. Black said:

"Broad street added last year a number of handsome and costly stores, and at present much finer and more imposing ones are being built. Messrs. D. & E. Mitteldorfer are building one, which will be broken-range, quarry-faced granite from ground to cornice line." -- From a newspaper item entitled “Architects Active – What Some of These Gentleman Have to Say About the Outlook,” Richmond Dispatch, April 4, 1890_

Described in the deed [of Black’s house] as being “in the form of a right-angle triangle,” the lot must have challenged Black’s imagination as how to fill it with something functional. His solution was generally to conform the footprint of the house to the shape of the lot, thus producing in effect a “right-angle triangle” house. In addition to its unusual shape, 1300 Floyd Avenue exhibits clean, sharp lines accentuated today by the loss of its porch. It was a modern building for 1889 Richmond, and exudes some hint of the Queen Anne style, which at the time was becoming very popular in Richmond.

Black died on March 23, 1892 at his home after a six-month illness. He was 57 years old. He was buried in Mount Cavalry Cemetery in Richmond. A longer essay on Bernard J. Black's life and work will appear in the Shockoe Examiner in the future.

Unfortunately, the newspaper article on Queen Anne Row from 1890 did not list which firm provided the millwork for the porches. This image of the center porch, 214 and 216 W. Main St., was provided by Dr. Charles E. Brownell, the former longtime head of the Architectural History Program at VCU. Charles's very informed perspective on the millwork is that it was most likely chosen by the architect, Bernard J. Black, from a local firm. The pattern of the porch design on Queen Anne Row could be found in millwork catalogs published at this time. The catalogs were widely circulated so local firms could easily produce them.

Charles explores in depth these types of architectural history topics each year at an annual lecture at VCU Libraries entitled "Artistic Mansions." The next "Artistic Mansions" is tentatively scheduled for 11 April 2026 and will take a good look at the Queen Anne style in Richmond. Many of the past lectures are available on YouTube. We appreciate his continued support and his willingness to share his knowledge in our investigations of Richmond's architectural history.

The Contractors

General Contractor

Advertisement from the 1889 Richmond city directory.

The stone contractor, “A. J. Brown, stone-work,” was Alonza J. Brown (1854-1937). By 1890, Brown had been a stone mason for twenty years and had established his own granite quarry. His work for the five houses on W. Main St included supervising the stone masons and supplying different types of stone, including grey granite, brownstone, and contrasting colors of limestone. Different combinations of stone were used in each building - read the detailed descriptions HERE.

An example of the Wray and Brown memorial work is the 25-foot-high obelisk placed in the plot of Dr. Hunter H. McGuire (1835-1900) in Hollywood Cemetery. The stone is blue granite from Wray's quarries in Chesterfield County. The excellent images were taken by Selden Richardson, architectural historian and one of the editors of The Shockoe Examiner.

Image of Landers that appeared with the obituary of the long-time city plumbing inspector in the May 15, 1926 issue of the Richmond Times-Dispatch. The same image was previously published in the April 17, 1921 issue of the RTD credited to Foster Studio.

... chief plumbing inspector for the city of Richmond, and connected with that office for three decades, died yesterday morning at 5:05 o'clock at the home, 2016 Hanover Avenue. The funeral will be from Sacred Heart Cathedral at 10 o'clock Monday morning, and burial will be in Mount Calvary Cemetery.

Mr. Landers, is survived by a widow, formerly Miss Nellie Enright, and the following children: Mrs. Thomas L. Cox, of Chester; Mrs. Charles Halbleib, of Norfolk: George and Thomas Landers, and Mrs. Philip Bannister, of Richmond. His first wife, who died many years ago, was Miss Lena Roscher, of Richmond. Mr. Landers was born in Richmond in 1851, and lived here all his life. He devoted his early business career to the plumbing business in Richmond.

The late inspector was for many years active in public matters, and was interested in fraternal and church affairs throughout his career. He was a member of Richmond Lodge of Elks, the Knights of Columbus, St. Mary's Social Union, Holy Name Society of Sacred Heart Cathedral, and was a member of the American Society of Sanitary Engineers, frequently representing Richmond city at the annual conventions of that society. He was considered an expert in his business and was frequently called upon for expert opinions. The various heads of the Department of Welfare and the City Health Board have frequently commended the late inspector for his loyalty and the efficient handling of the duties in connection with his office.

"Another specialist, Richmond iron founder, Asa Snyder, cast the grills and fencing along with the magnificent cast iron atrium, a masterpiece of cast iron architecture. Snyder, a New York immigrant, was a leader in the development of architectural cast iron in Richmond."

"...the atrium is an outstanding example of and a high point for cast iron architecture in Richmond."

The building’s last renovation, which took place in the 1980s, superimposed a polychrome paint scheme throughout the major historic spaces. Based on historical finish analyses, our design restores the original palette: off-white plaster walls and ceilings, oak woodwork, and painted wood graining on cast iron elements in the atrium. We also restored the atrium laylight and replaced the skylight above with an energy-efficient reproduction.

Due to their long history and contributions to the city's architectural heritage, Asa Snyder & Co. probably deserves its own blog post (or better yet, a book-length study). The Shockoe Examiner will explore their history at length in the future. But for now, the goal of this essay is to keep their profile as concise, but still complete, as possible.

Born in 1825, he early clerked in his farmer father's country store, went to school at an academy, worked in New York City, was in business in Pennsylvania, and returned home to farm a while.

In 1851, he visited Richmond with his brother-in-law, Foundryman A. J. Bowers. Charmed with the city, they leased a lot opposite the Tredegar Iron Works on the James and Kanawha Canal for 10 years, built and began to make stoves.

In 1855, they branched out to do ornamental iron work. Their first effort, and the first in Richmond, was the lavish iron-decked facade of old Ballard House hostelry, which they adorned with cast-iron pillars, veranda, balconies, cornices, fence, and gate. Between '59 and '60, Snyder similarly trimmed the Spotswood, another fashionable hotel, and later many Main Street business houses, which still wear Snyder designs on their much-painted facades, whose scrolls, cornices, and trimmings have come to look wooden with many years and much paint.

Two branches - stoves and iron work - were too much for the firm and Mr. Snyder and Mr. Bowers dissolved it in 1856. But Snyder continued at stove-making until 1865, at Tenth and Cary Streets. He continued through the war, when his foundry, "being the only works in the Confederate States, prepared to make outfits for the camps, he was employed by the Confederate government and did faithful work for the cause of his adopted State," according to his obituary of August, 1884, in the Dispatch. His daughter, Miss Annie Lee Snyder, explained to Miss McCormack [Helen McCormack (1903-1974), then head of the Valentine Museum] that he made iron utensils, kettles and such for the Confederate army, was paid largely in produce, built a supplementary warehouse adjoining his Fourth Street home and shared his earnings of produce with his neighbors.

Thirty-five years ago this establishment was founded by the late Asa Snyder in a very moderate way, but it gave genuine evidence of enterprise from the start, and in a few years it became a noted landmark of the business industry. War, fire, and financial strife, have battered at its doors, but it still stands a monument to the enterprise of its founder. Its contributions to the trade reflect the greatest credit on the mechanical skill of those employed in its several constructive departments. They find a large and steady demand from Virginia and West Virginia, North and South Carolina, for their beautiful and reliable goods of architectural designs. They employ sixty hands and have a capacity for making five tons of castings per hour.

Their specialties are all kinds of galvanized, cast and wrought iron used in building, which embraces vault doors, elevators, fence and balcony railings, verandas, skylights, cornices, window hoods, steeples, &c. They are also manufacturers of Hayes' Patent Skylight, Hyatt's Patent Area Light, for which they control Virginia.

Messrs. Asa K. Snyder and Benj. J. Atkins comprise the present firm of Asa Snyder & Co. They were both members of the firm at the time of the death of Mr. Asa Snyder, in 1884, and have continued under the same firm name.

Mr. Asa K. Snyder was born and raised here and was brought up in the iron trade. He is also in the pig iron and foundry supply brokerage business.

Mr. Atkins resides in Manchester. He has been connected with this house for twenty years and has been a partner in the concern since 1877.

Its record includes the furnishing of structural iron for the following buildings, among the many extensive orders of the past few years: City Hall, Masonic Temple, All Saints' Episcopal Church, store of Julius Meyer & Sons, Richmond; library in the new State Department building, Washington, D. C.; Enterprise Building, Fredericksburg; First Presbyterian Church, Hughes Building, the Wither's Building, and the Post Building, Newport News; True Reformer's Hall, and a theatre at Norfolk; Bachelor's Quarters, Fortress Monroe; W. P. Dickerson's Hall, Farmville, Va..

.jpg)