Ginter House, 901 W. Franklin St., Richmond, Virginia, built 1888-1892, is one of the city's most architecturally significant structures and is considered the finest example of Richardsonian Romanesque architecture in Virginia. The house was built for Lewis Ginter, a tobacco magnate and one of the wealthiest men in late 19th-century Virginia. It briefly served as Richmond's first public library (1925-1930) and has been the main administrative building on the Monroe Park campus of Virginia Commonwealth University since 1930.

In the mid-1880s, Ginter acquired a country house called "Westbrook" in Henrico. Just before work on his house on W. Franklin was begun, "Westbrook," originally a large farmhouse, was turned into a Queen Anne mansion by Richmond architect Edgerton Rogers (1861-1901) known to most as the architect of Maymont, the grand house of Major James H. Dooley and his wife Sallie May Dooley. "Westbrook" and its property were converted to use as a psychiatric hospital in 1911. The house was demolished in 1975.

Item from The Critic and Record, a newspaper published in Washington, D. C., March 16, 1888.

For his house on W. Franklin St., located only blocks from the city's center, Ginter chose Washington, D.C. based architects Harvey L. Page (1859-1934) and William Winthrop Kent (1860-1955) to design his suburban mansion. Page was the architect while Kent served as the chief ornamentalist.

Drawing of Ginter House as it appeared in Building: An Architectural Weekly, vol.9, no. 3, July 21, 1888. The image was spread over two pages and lists Harvey L. Page and W. W. Kent (William Winthrop Kent) as architects.

The west side of Ginter House, circa 1900, image from Special Collections and Archives, VCU Libraries.

An article on houses being constructed in Richmond included

a passage on the building of Ginter House. This is from the Feb. 23, 1890 issue

of the Richmond Times-Dispatch:

Among the handsome buildings in construction is Mr. Lewis Ginter's residence on Franklin street, above Shafer. It will be the largest and costliest private house in Virginia. Besides closets, servants' quarters, &c., it contains more than fifty rooms. The material of the house is sand-faced brick and brownstone, with a glazed tile roof and copper ornaments. A huge tower will surmount the western end, and on the eastern side of the building will be a conveniently arranged carriage entrance. The interior is to be fitted up in the most gorgeous manner; each room will be finished in hard polished woods, no two rooms alike, and the floors inlaid in various pretty designs. The outside porches will be laid in tiles. In the rear of the house will be large stables, handsomely appointed. In its present incomplete condition the building, which is virtually only two stories high, looks very odd, and a great many people who see it want to know - to use one of the slangy criticisms - "What Mr. Ginter is trying to get at." But when the house is seen in all its unique architectural beauty, with ornaments, trimmings and finishings, the exclamations will be of admiration.

Ginter House has many architectural features found in Richardsonian-style buildings. The exterior has been best described by Kerri Culhane

in her 1992 master's thesis "The

Fifth Avenue of Richmond": The Development of the 800 and 900 Blocks of

West Franklin Street, Richmond, Virginia, 1855-1925." Culhane wrote:

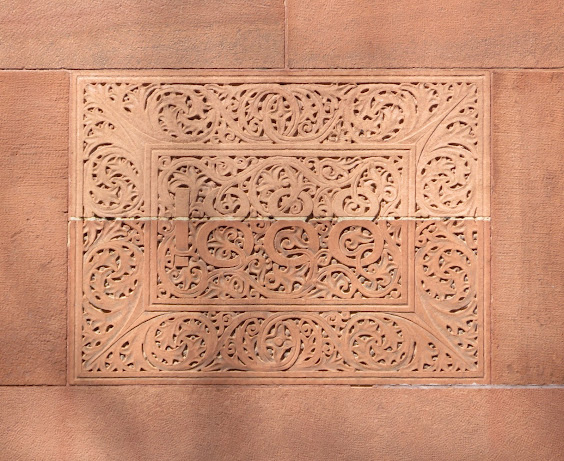

It would take nearly four years to complete the massive mansion. As completed by 1892, the house alone assessed at $60,000.00, nearly eight times the value of the average townhouse on the street, and three times as much as the largest houses to date. The main block of Ginter House is three-and-one-half stories in height, and was built on a center-hall plan. The wide living hall is flanked by parlors. The east parlor is articulated on the exterior as a square projecting bay. The west parlor is partially comprised in the polygonal three-story tower. The stone and brick work is executed in a hierarchy of materials. The basement is clad in rock-faced brownstone. The first floor is finished in pecked brownstone. Upper floors are pressed brick executed in both stretcher courses and basket weave patterns. Molded brick and drilled stone panels are inset into the exterior. The east elevation contains a Syrian arch over a recessed entrance and a two-story bowed bay. The roof is clad in Spanish tiles.

Parlor of Ginter House, May

1902 edition of Architects' and Builders' Magazine.

The lavish interior of the house is described here by Dale Wheary in her 1993 graduate seminar paper, "The Sense of Truth and Beauty: Harvey L. Page Builds a House for Ginter." Wheary writes that the interior of Ginter House:

... projects a wonderfully integrated character which seems quite in harmony with the styling of the exterior.

The comfortably sized principal rooms are arranged around two spacious halls intersecting to form a T. From the Franklin Street side: the front door opens into the entrance hall paneled in quarter-sawn oak with a richly stenciled frieze, presently in colors said to be based on the original wall cover still intact in the foyer. The fireplace surround in this hall is carved stone in a typical Romanesque foliate design. The parquet border in the all is intact.

Hall of Ginter House, May 1902 edition of Architects' and Builders' Magazine.

Wrought iron door handles on the front entrance of Ginter House supplied by the G. Krug and Sons ironwork firm of Baltimore. Photo by Clement Britt.

One of the most important features of the house is the ironwork.

Records from the Baltimore ironwork firm of G. Krug and Sons collection

housed at the Maryland Historical Society document that the ironwork at

Ginter House was provided in 1890 by the Krug and Sons firm. The

records show drawings for individual iron pieces for Ginter House and

mention who in the firm designed them. The ironwork design was

probably selected by William Winthrop Kent who would publish his book Architectural Wrought-Iron, Ancient and Modern

in 1888, the year work on Ginter House began. Kent's book is

illustrated with examples of the Krug firm's work in Richardson

buildings in Washington, D.C.

In a 2008 research paper on the ironwork of West Franklin Street, Gabriel Craig, then a graduate student at VCU, wrote that records at the Maryland Historical Society note that the G. Krug and Sons firm provided Ginter House "24 wrought iron basement window grilles, 3 wrought iron door grilles, 6 wrought iron sidelight grilles, 6 wrought iron window grilles, 6 wrought iron window grilles on the east side of the house, 8 wrought iron door straps and hinges, and wrought iron door handles escutcheons, knobs, and bells throughout the house." Some of this ironwork at Ginter House can still be seen today. Craig also writes that "George W. Parson, the [local Richmond contractor and builder] of Ginter House, ordered 3 ornamental forged bell escutcheons with electric pushes and screws. This is significant because it indicates that Ginter House, rather than the Jefferson Hotel [as some have suggested] was the first building in Richmond to have electricity."

The date of 1888, when work on the house was first begun, can be seen carved into the brick on the chimney façade on the Shafer Street side of the building.

An article in the Richmond State, dated March 13, 1888, announced that the building's construction had begun. The article noted that the stone firm of "Hutcheon and Donald" were to be the stone contractors.

The Hutcheon and Donald firm had a stone quarry three miles outside of Richmond. What kind of brownstone was used? A March 20, 1889 article in the Richmond Dispatch said that

the proposed Masonic Temple building that was to be built on Broad Street will use "Potomac red sandstone, known as

Seneca, same as being used on Major Lewis Ginter's new house."

[I must note that the proposed stone for the Masonic Temple building may have changed from the Potomac red sandstone to brownstone from West Virginia. A news article in the Richmond Dispatch, June 3, 1890, reported that the Masonic Temple building is to have "the front up to the

first floor will be Alderson brownstone," - which was from West

Virginia.]

Bailey T. Davis (1827-1897), a long-time brick contractor, provided the bricks. While most work was completed by the end of

1891, an article in the February 10, 1892 issue of the Richmond Dispatch reported "a magnificent entertainment" celebrating the opening of the Ginter's mansion and noted that "fully 500 persons"

were present including Gov. Phillip W. McKinney of Virginia and J.

Taylor Ellyson, the mayor of Richmond.

Ginter never married. His grand mansion was home to both him and his niece, Grace Arents (1848-1926). Ginter died on October 2, 1897. Newspaper accounts of the time wrote that he was worth over $10 million. His resting place is in Hollywood Cemetery in a mausoleum with windows designed by Tiffany Studios. Most of his fortune, including Ginter House, was left to Arents, who continued his philanthropy work in Richmond. She moved to Bloomingdale Farm north of Richmond in the 1910s. That property eventually became the Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden.

Ginter House from the Shafer Street side when the building was known as the Administration Building of Richmond Professional Institute, 1940s.

Ginter never married. His grand mansion was home to both him and his niece, Grace Arents (1848-1926). Ginter died on October 2, 1897. Newspaper accounts of the time wrote that he was worth over $10 million. His resting place is in Hollywood Cemetery in a mausoleum with windows designed by Tiffany Studios. Most of his fortune, including Ginter House, was left to Arents, who continued his philanthropy work in Richmond. She moved to Bloomingdale Farm north of Richmond in the 1910s. That property eventually became the Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden.

From Richmond Richmond , Virginia Richmond , Va.

Illustrations of Ginter House were widely published in souvenir and

booster publications of Richmond. The style of the house influenced many

later buildings in the city - though none were as large or grand in

their design as Ginter House.

From 1924 through 1930, Ginter House served as home to the City of Richmond's first public library. This library was segregated - Black Richmonders could not use its facilities. In 1925 the city opened the Rosa D. Bowser Library for African Americans. Named for Rosa L. Dixon Bowser (1855-1931), a civic leader who was considered the first African American female school teacher in Richmond, the library was located in the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the YWCA at 515 N. 5th Street.

The library in Ginter House also served the students of the Richmond School of Social Work and Public Health which had moved in 1925 to a building across the street from d Founder's Hall. This same school purchased Ginter House in 1930 and the adjoining property in the back. Ginter House became a multi-function building for the school - it housed a small library, classrooms, and offices. As the school grew, it became exclusively an administrative building for the offices of the provost, vice presidents, and other school officials. An east wing was added as part of a WPA project in 1939 and a west wing was added at the back of the building in 1949.

In 1930 the school became Richmond Professional Institute (RPI), which would in 1968 merge with the Medical College of Virginia to become Virginia Commonwealth University.

As of 2025, Ginter House houses the Office of the Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs and other administrative departments. But the building is more than an office building. It It is the principal jewel of the many historic houses along the 800 and 900 blocks of W. Franklin St., VCU's "open-air architectural museum."

- Ray Bonis

Bibliography:

Brian Burns, Lewis Ginter: Richmond's Gilded Age Icon, 2011.

Ray Bonis, and Jodi Koste, and Curtis Lyons. Virginia Commonwealth University. Charleston, SC, Arcadia, 2006.

Doug Childers, Ginter House: A mansion that helped shape Richmond’sarchitecture is now part of a university, April 3, 2017, Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Gabriel Craig "William Winthrop Kent's Architectural Wrought Iron on the 800 and 900 Blocks of West Franklin Street, Richmond, VA: 1885-1895." Seminar paper prepared for Dr. Charles Brownell (VCU Dept. of Art History) -- Spring, 2008. Housed in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library, VCU Libraries

Linda George, "Richardsoinan Architecture in Washington D.C. and Richmond, Virginia Seminar paper prepared for Dr. Charles Brownell (VCU Dept. of Art History) -- Fall, 2004. Housed in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library, VCU Libraries.

Linda George, "Decorative Arts on VCU's West Franklin Street: A tour for the Society of Architectural Historians", April 21, 2002. Richmond, Va. : Dept. Of Art History, School of the Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2002. Available at the Special Collections and Archives dept. of VCU Libraries.

Lewis Ginter: A Quiet Contribution, produced by Henrico County Public Relations and Media Services, 2008. Internet Access http://www.co.henrico.va.us/departments/pr/channel-17/online-programs/

Paul. N. Herbert, The Jefferson Hotel: The History of a Richmond Landmark, 2012.

Mary H. Mitchell and Robert S. Hebb. A History of Bloemendaal Richmond, Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden, Inc., 1986.

Samuel J. Moore, The Jefferson Hotel, a Southern Landmark. Richmond, 1940.

Pierce, Don. One Hundred Years at the Jefferson: Richmond's Grand Hotel, a History. Richmond, Page One Inc., 1995.

David D. Ryan and Wayland W. Rennie. Lewis Ginter's Richmond : [Bellevue, Bloemendaal, Ginter Park, "Laburnum," Laburnum Park, Sherwood Park, the Jefferson Hotel, "Westbrook," post Civil War to present.] Richmond, Va. :Whittet & Shepperson, 1991.

Douglas E. Taylor, Suburban Reflections: A Review of the Attractive Suburban Property Belonging to the Estate of the late Major Lewis Ginter. Presented by Douglas E. Taylor, real estate agent. Richmond, I. N. Jones & Son, ca. 1900.

Dale Wheary, "The Sense of Truth and Beauty: Harvey L. Page Builds a House for Lewis Ginter" from The Architecture of Virginia: Abstracts of the 1994 Architectural History Symposium, Department of Art History, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1994. Available at the Special Collections and Archives dept. of VCU Libraries.

Gabriel Craig "William Winthrop Kent's Architectural Wrought Iron on the 800 and 900 Blocks of West Franklin Street, Richmond, VA: 1885-1895." Seminar paper prepared for Dr. Charles Brownell (VCU Dept. of Art History) -- Spring, 2008. Housed in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library, VCU Libraries

Linda George, "Richardsoinan Architecture in Washington D.C. and Richmond, Virginia Seminar paper prepared for Dr. Charles Brownell (VCU Dept. of Art History) -- Fall, 2004. Housed in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library, VCU Libraries.

Linda George, "Decorative Arts on VCU's West Franklin Street: A tour for the Society of Architectural Historians", April 21, 2002. Richmond, Va. : Dept. Of Art History, School of the Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2002. Available at the Special Collections and Archives dept. of VCU Libraries.

Lewis Ginter: A Quiet Contribution, produced by Henrico County Public Relations and Media Services, 2008. Internet Access http://www.co.henrico.va.us/departments/pr/channel-17/online-programs/

Paul. N. Herbert, The Jefferson Hotel: The History of a Richmond Landmark, 2012.

Mary H. Mitchell and Robert S. Hebb. A History of Bloemendaal Richmond, Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden, Inc., 1986.

Samuel J. Moore, The Jefferson Hotel, a Southern Landmark. Richmond, 1940.

Pierce, Don. One Hundred Years at the Jefferson: Richmond's Grand Hotel, a History. Richmond, Page One Inc., 1995.

David D. Ryan and Wayland W. Rennie. Lewis Ginter's Richmond : [Bellevue, Bloemendaal, Ginter Park, "Laburnum," Laburnum Park, Sherwood Park, the Jefferson Hotel, "Westbrook," post Civil War to present.] Richmond, Va. :Whittet & Shepperson, 1991.

Douglas E. Taylor, Suburban Reflections: A Review of the Attractive Suburban Property Belonging to the Estate of the late Major Lewis Ginter. Presented by Douglas E. Taylor, real estate agent. Richmond, I. N. Jones & Son, ca. 1900.

Dale Wheary, "The Sense of Truth and Beauty: Harvey L. Page Builds a House for Lewis Ginter" from The Architecture of Virginia: Abstracts of the 1994 Architectural History Symposium, Department of Art History, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1994. Available at the Special Collections and Archives dept. of VCU Libraries.

- Ray Bonis

.jpg)

2 comments:

This is a fabulous piece! Thanks for putting it back in circulation! There is no excuse for it being withdrawn from our online collections. The building has been the womb and hub of VCU's emergence. I enjoyed it so much, particularly since so much of my own story took place in so many corners of this building and with so many of its occupants, beginning in the Fall of 1953. Best wishes, Ed

Thanks for sharing useful information for us.I really enjoyed reading your blog, you have lots of great content.Please visit here

https://www.lcrenovation.co.uk/loft-conversion-in-dulwich/

House Renovations in Dulwich

Post a Comment