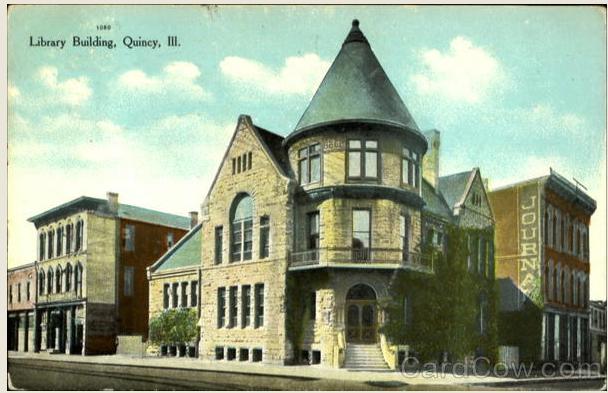

The Quincy Public Library in Quincy, Illinois as it

appeared in The Daily Times (Richmond, Va) on July 2, 1888.

Why would a Richmond newspaper run an image of a new building in Illinois? While looking for something else I came across several issues of the Daily Times where they published images of newly constructed buildings outside of Virginia. Those same pages had a listing of local Richmond architects and builders. Was one of those architects or builders responsible for calling attention to these out of state buildings? Or was it a case of some sort of wire subscription to provide copy to newspapers nationwide? I do not know the answer, but, as we say at VCU, it is worth pursuing.

The building is in the Richardsonian style. That same year in Richmond construction began on Richmond's first Richardsonian style building, Ginter House, at 901 Park Ave. It actually became the home of Richmond's first public library in 1925. The lasted for five years before the building was purchased by the school that became Richmond Professional Institute (now VCU).

A postcard image of the library - postmarked 1909.

And what happened to this interesting building? I emailed the library at Quincy, Ill. and asked - here's the response I received:

The old Free Public Library was built in 1888 by F. W. Menke Co. [a stone company]. The building has not been demolished. It still stands on 4th and Maine, and is now the Gardner Museum of Architecture and Design.

Thanks for asking, and for the postcard image.

Sincerely,Nancy DolanQuincy Public Library

I think it is great their building is still around. I wish Richmond kept more of its old buildings! Check out the link to the Gardner Museum - it has more images of this building and mentions the architectural firm.

- Ray B.

6 comments:

Where does Grace Arents' free library (now the William Byrd Community House) fall into the timeline?

That's a good question. A real history of the city's libraries needs to be written. The best thing I've seen online is this:

http://www.richmondpubliclibrary.org/content.asp?contentID=54

The Arents Free Library opened between 1903 to 1911 depending on your online source. We'll try to find something more definitive about this. The Arents library was not a public library in that it was not sponsored by any locality (like the City of Richmond)- it was more of a neighborhood private library. Like of all of Richmond, it was segregated and did not permit blacks (who at that time were not living in Oregon Hill).

If you go to the link above you'll see there were other libraries operating in the city about the same time - but the city's first real public library, operating with city funds, began at the Ginter House before moving to the Dooley Library which is now encased in the Richmond Public Library on Franklin Street.

From a book on Richmond postcards (co-authored by myself and Tom Ray) we learn:

The (James H.) Dooley Memorial Library, 101 E. Franklin Street, was built 1929-1930. The library was an Art Deco style building designed by Baskervill and Lambert. A new and much larger Richmond Public Library building built in 1972 now surrounds the old building. The original entrance hall remains as the lobby of the eastern half of the new building. Funding for the Dooley Library originated from a $500,000 bequest by Sallie May Dooley (1846-1925), wife of Major James H. Dooley (1841-1922). The Dooleys gave their large estate, Maymont, to the City of Richmond to be used as a park after their death.

Richmond was one of the last cities of its size in the nation to build and operate a public library. In 1901 Andrew Carnegie’s offer to donate $100,000 to the City of Richmond to erect a public library was initially accepted by City Council. Despite efforts by supporters of a public library, led by Robert Whittet, Sr. of the publishing firm Whittet and Shepperson, funding by the city was never allocated. Carnegie’s demands that the city find and purchase a site and allocate $10,000 a year for the maintenance for a library were considered too costly by the city.

Those early efforts did lead to the formation of a citizens’ campaign for a library in the 1910s and 1920s. As public support grew, City Council finally agreed to fund a public library. Richmond’s first public library operated from 1924 to 1930 at 901 W. Franklin Street, the former residence of Major Lewis Ginter (1824-1897). In segregated Richmond African Americans could not use the library. In 1925 the city opened the Rosa D. Bowser Library for African Americans. Named for Rosa L. Dixon Bowser (1855-1931), a civic leader who was considered the first African American female school teacher in Richmond, the library was located in the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the YWCA at 515 N. 5th Street.

That's a good question. A real history of the city's libraries needs to be written. The best thing I've seen online is this:

http://www.richmondpubliclibrary.org/content.asp?contentID=54

The Arents Free Library opened between 1903 to 1911 depending on your online source. We'll try to find something more definitive about this. The Arents library was not a public library in that it was not sponsored by any locality (like the City of Richmond)- it was more of a neighborhood private library. Like of all of Richmond, it was segregated and did not permit blacks (who at that time were not living in Oregon Hill).

If you go to the link above you'll see there were other libraries operating in the city about the same time - but the city's first real public library, operating with city funds, began at the Ginter House before moving to the Dooley Library which is now encased in the Richmond Public Library on Franklin Street.

From a book on Richmond postcards (co-authored by myself and Tom Ray) we learn:

The (James H.) Dooley Memorial Library, 101 E. Franklin Street, was built 1929-1930. The library was an Art Deco style building designed by Baskervill and Lambert. A new and much larger Richmond Public Library building built in 1972 now surrounds the old building. The original entrance hall remains as the lobby of the eastern half of the new building. Funding for the Dooley Library originated from a $500,000 bequest by Sallie May Dooley (1846-1925), wife of Major James H. Dooley (1841-1922). The Dooleys gave their large estate, Maymont, to the City of Richmond to be used as a park after their death.

Richmond was one of the last cities of its size in the nation to build and operate a public library. In 1901 Andrew Carnegie’s offer to donate $100,000 to the City of Richmond to erect a public library was initially accepted by City Council. Despite efforts by supporters of a public library, led by Robert Whittet, Sr. of the publishing firm Whittet and Shepperson, funding by the city was never allocated. Carnegie’s demands that the city find and purchase a site and allocate $10,000 a year for the maintenance for a library were considered too costly by the city.

Those early efforts did lead to the formation of a citizens’ campaign for a library in the 1910s and 1920s. As public support grew, City Council finally agreed to fund a public library. Richmond’s first public library operated from 1924 to 1930 at 901 W. Franklin Street, the former residence of Major Lewis Ginter (1824-1897). In segregated Richmond African Americans could not use the library. In 1925 the city opened the Rosa D. Bowser Library for African Americans. Named for Rosa L. Dixon Bowser (1855-1931), a civic leader who was considered the first African American female school teacher in Richmond, the library was located in the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the YWCA at 515 N. 5th Street.

That's a good question. A real history of the city's libraries needs to be written. The best thing I've seen online is this:

http://www.richmondpubliclibrary.org/content.asp?contentID=54

The Arents Free Library opened between 1903 to 1911 depending on your online source. We'll try to find something more definitive about this. The Arents library was not a public library in that it was not sponsored by any locality (like the City of Richmond)- it was more of a neighborhood private library. Like of all of Richmond, it was segregated and did not permit blacks (who at that time were not living in Oregon Hill).

If you go to the link above you'll see there were other libraries operating in the city about the same time - but the city's first real public library, operating with city funds, began at the Ginter House before moving to the Dooley Library which is now encased in the Richmond Public Library on Franklin Street.

From a book on Richmond postcards (co-authored by myself and Tom Ray) we learn:

The (James H.) Dooley Memorial Library, 101 E. Franklin Street, was built 1929-1930. The library was an Art Deco style building designed by Baskervill and Lambert. A new and much larger Richmond Public Library building built in 1972 now surrounds the old building. The original entrance hall remains as the lobby of the eastern half of the new building. Funding for the Dooley Library originated from a $500,000 bequest by Sallie May Dooley (1846-1925), wife of Major James H. Dooley (1841-1922). The Dooleys gave their large estate, Maymont, to the City of Richmond to be used as a park after their death.

According to Charles Pool:

Hi Scott,

According to the nomination report for the Oregon Hill Historic District (on file at the Va. Dept. of Historic Resources):

In 1894 Grace Arents founded a library in the house at 230 S. Laurel Street. In 1899 in became the first free library in Richmond. In 1908, she built a larger library facility, the Arents Free Library at 224 S. Cherry Street [now the William Byrd Community House]... The library on Cherry Street became part of the city library system in May 1927, but oversight responsibility was turned over to the St. Andrew's Assoc. in June 1946 ...

http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Cities/Richmond/127-0362_Oregon_Hill_HD_1991_Final_Nomination.pd

Post a Comment